The world war on statues

“As a social psychologist, it is impossible not to notice how little our behaviour has evolved from other anti-establishment movements, some hundreds of years old.”

Strangely enough, it seems that the newly emergent world war is one fought against statues. As most urban dwellers these days know nothing about those whose statues they pass by daily, or little of the characters their street names are based on, they identify statues that ought to be under attack from the alleged offenses highlighted by various instigators and leaders of the movement, who summon their troops on the Internet.

This is a proxy war, where statues are a pretext, standing in for the higher status group. It is this superior status and its social legitimacy that protesters are attacking. This is a global war, because it has been universalized, and because there is no society without an ongoing conflict for social status between groups. Recent events have just provided ammunition to those who perceive themselves as inferior in status. Furthermore, one may call this a revolutionary war, as contesters seek no less than the replacement by themselves of the established elite, which defends these statues.

This is a proxy war, where statues are a pretext, standing in for the higher status group.

Revolutions have not amounted to much in the last 20 years, but the long recession and uncertainty that follows the Corona crisis offers fertile ground, promising a deep shakedown of social and national hierarchies. Some of these hierarchies are fundamental to the identity of the West as we know it, and it is not clear what will replace them. Contesters frame current Western establishments as the descendants of colonizing, undemocratic and racist powers, forgetting that they also inherit the progressives who were against tyranny, slavery or colonization, who eventually had the upper hand.

Of course, not all historical discrimination and in particular not all inequality has been eliminated. The means and capabilities to deliver perfect equality and fairness vary greatly, however, and are subject to debate across groups and societies.

However, ethical universalism, defined as the moral principle that all persons ought to be treated with equal and impartial positive consideration for their respective goods or interests does indeed seem to have conquered the world and become the global norm, a subject I addressed in 2019 in my S.M. Lipset lecture. A revolution aiming to achieve equal status for all cannot be stopped in its tracks or challenged. Already in 1935, Alexis de Tocqueville wrote that, “The gradual development of the equality of conditions is therefore a providential fact, and it possesses all the characteristics of a divine decree: it is universal, it is durable, it constantly eludes all human interference, and all events as well as all men contribute to its progress”[1].

Is this about freedom?

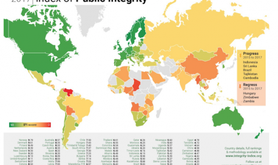

Tocqueville, an observer of a three-act revolution (1789, 1830 and 1848) also noted that this drive for equality surpasses that for freedom, a deep insight that many of his conservative or liberal commentators chose to forget[1]. No one weighs up today, as they did not weigh up in any previous revolution, whether or not the alternative elite is truly more capable of delivering ethical universalism than that of the ancien regime. Most former colonial countries are ruled by kleptocrats today, whether they are democrats or autocrats, and the explanatory power of the colonial legacy has lost some of its shine [2].

It is nice to unleash national and social liberations, but the more radical they are, the faster they engender new forms of subjugation. Corruption replaces old cleavages as the major universal source of discrimination. We call this in political science the primacy of politics: it's all about power, who has power generates economic opportunities. How many of those who besiege the statues want ethical universalism, and how many just want superior status for themselves? The answer varies from country to country and from group to group, but any objective observer of the national and social liberations of our times cannot fail to notice that they more often than not produce new status groups instead of eliminating status-based societies.

The liberal Western media these days gives however the impression that we witness a genuine universal quest for ethical universalism. They might as well expect the man who recovers the ball from the rugby pile to cut it into chocolate-like tables to give the others an equal share instead of scoring.

Anti-establishment psychology

Therefore I would refrain, when statues are a pretext as such, to discuss the merits of individual statues and characters and individual justifications, since the overall drive requires little more motivation than the existence of present discrimination itself. As a social psychologist, it is impossible however not to notice how little our behaviour has evolved from other anti-establishment movements, some hundreds of years old.

The European Reformation, which criticized Catholicism for promoting superstition and corruption, massacred religious statues: you can still see these today from England to Germany, and the scars left by this progressivism blended with an equally profound barbarism. The Enlightenment representatives who made the French Revolution beheaded the kings of Notre Dame and destroyed the giants of the mortuary basilica of Saint Denis. In the Spanish Civil War of the last century, the promoters of equality and secularism massacred a score of Jesus, Virgos, knights, prelates, angels and saints in magnificent churches that they reduced to ruin. The Russian early twentieth century novelists left unforgettable accounts of serfs who commenced their liberation after the Bolshevik revolution by removing the heads of nudes from the parks of their devastated oppressors' mansions. In the twenty-first century, Islamic fundamentalists in Asia, Africa and the Near East destroyed ancient monuments and cities simply as symbols of the Western value system, although the civilizations which produced Palmyra or Timbuktu have long gone and were entirely different one from another.

Should we, however, endorse this behavior in the twenty-first century? You can appreciate the Reformation, side with with the French or Spanish Republicans, be against servitude and a progressive and still fail to see the enlightened and rational side of the attack on the statues.

Tit for tat

Rather it is the uniformity of behaviour from left to right and from the secular to the fundamentalist which is striking, and I believe, not positively. We can't rewrite history at every moment to make it fair: this idea is a dangerous dystopia. What we are is made of is what we were before, as a Gothic church has grown over a Romanesque choir, which stood on two remaining columns of the Roman temple, themselves placed on an older foundation of a Neolithic people. We cannot, even if the Neolithic people made human sacrifices, or the Romans had slaves, or during the Romanesque times the church burned heretics and so on and so forth – remove these foundations, because the most advanced architectural expression, the Gothic tower rests on them. T.S Eliot, wrote aptly that:

Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future,

And time future contained in time past.

If all time is eternally present

All time is unredeemable.

We can't clean up history after ourselves, like Stephen King's Langoliers that physically devour the world of the previous second to make way for the current one.

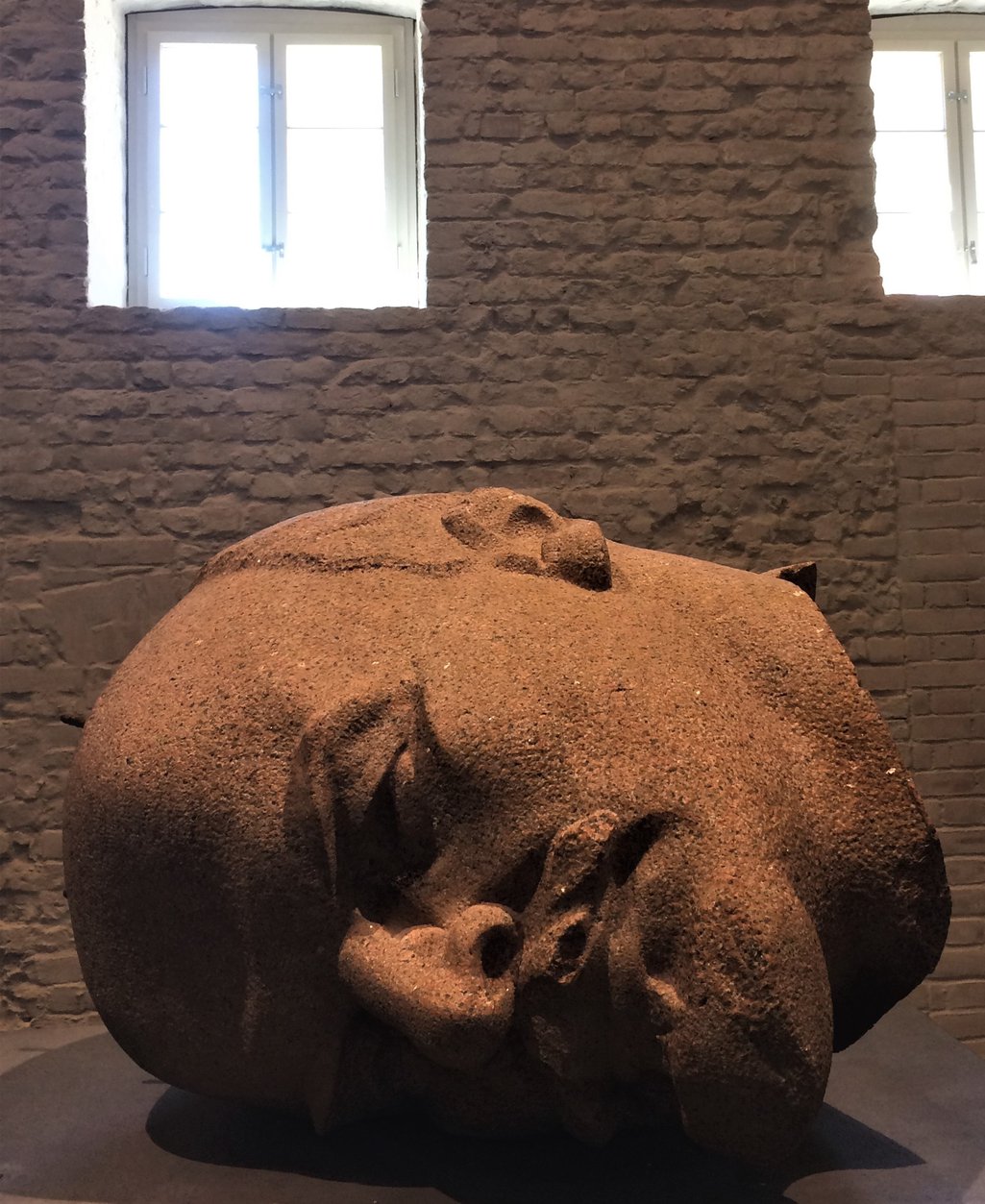

Of course, one might say that statues justifiably attract political anger, since they have been the object of intense political manipulation. Various political regimes paved themselves with statues. In the comedy Goodbye, Lenin, the huge 20-meter statue of Vladimir Ilyich is evacuated across the Berlin skyline by a helicopter, signalling a change of regime. In real life, the three- head of the statue was cut off and buried for several years in a forest in Brandenburg. More recently, Lenin’s head was dug up and placed in a new museum in Spandau citadel in the company of romantic portraits of these historical leaders, Whilhelmian, National-Socialist and many other statues, spaced along an alley in the Tiergarten park. My favorite is a headless knight, who carefully holds his helmet under his arm. You can see a selection in my pictures.

One can and should change the explanations of the statues, or their place, or build new statues, but to cut off the heads of old ones and ask for the annihilation of the past does not seem progressive to me.

Taking sides

Each of us is called, unfortunately, to take sides in any revolution.

I am attracted to the side of the statues largely because I do not like what attacking statues does to people. Whoever blows up a monument or ties the rope around the neck of a statue, for whatever reason, does not advance civilization, but relapses into old behavioral patterns which should not make humanity really proud.

You cannot manifest for progress and act as any barbarian would have done hundreds of years ago. We must stand between the statues and the crowds that attack them not because every statue is necessarily worthy, but because every man who melts into a crowd is a lost man for civilization. We must move the fight against discrimination onto other fronts than statues.

[1] de Tocqueville, A. (1954). Democracy in America: The Henry Reeve Text as Rev. by Francis Bowen, Now Further Corrected and Ed. with a Historical Essay, Editorial Notes, and Bibliographies by Phillips Bradley. Vintage Books: 6

[2] Tocqueville, Alexis de (1967). L'Ancien Régime et la Révolution Paris : Gallimard, coll. «Folio» : 317

[3] Mungiu-Pippidi, A. (2015). A Quest for Good Governance. How Societies Build Control of Corruption

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.